Originally posted at the MIT Center for Civic Media blog.

By Ethan Zuckerman and Erhardt Graeff

One of the best tricks educators can use is the technique of pulling students out of the classroom to encounter the issues we’re studying in the “real world.” So it’s a gift when an artist of the calibre of Anna Deavere Smith opens a new work in Cambridge just as the semester is starting. And given that our lab, the Center for Civic Media, studies how making and disseminating media can lead to civic and social change through movements like Black Lives Matter, a three-hour performance about the school-to-prison pipeline is an unprecedented pedagogical gift. A dozen of us made our way to the American Repertory Theatre at the end of August for a performance we’ll likely discuss for the rest of the academic year.

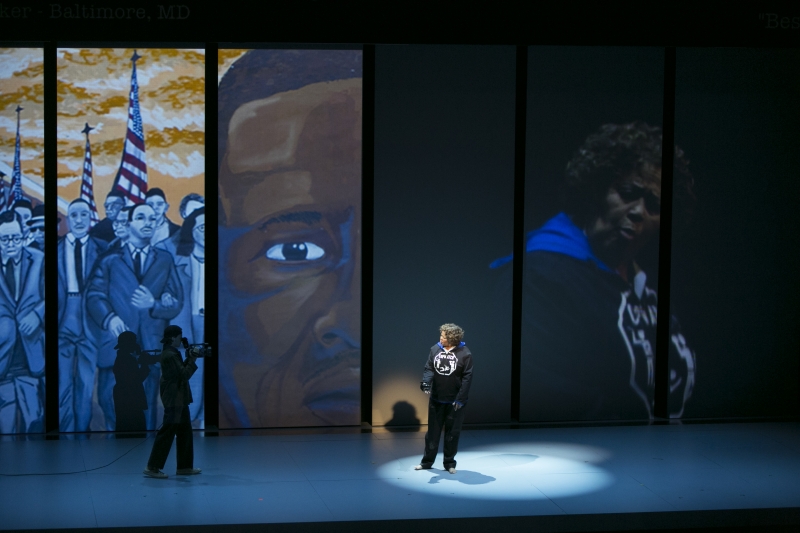

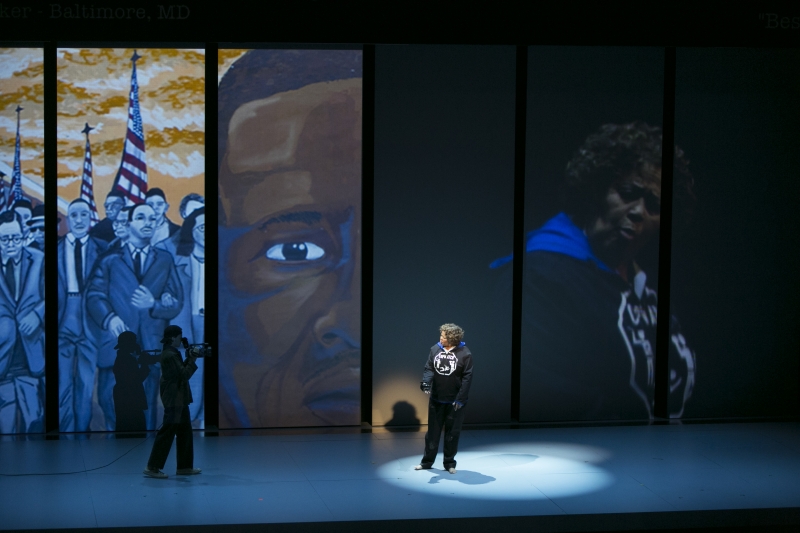

Deavere Smith’s work is often referred to as “documentary theatre,” and Notes From The Field: Doing Time In Education follows a model she’s rightly been celebrated for. Portraying individuals she’s interviewed while researching a controversial topic, she recreates their physical tics and speech patterns on stage, telling their stories—and the work’s larger narrative—through their original words.

Part of what makes this work is Deavere Smith’s ungodly skill at mimicry. As it happened, the first character she portrayed during Notes From The Field is a friend of Ethan’s—Sherrilyn Ifill, director of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund—and when he closed his eyes, the rhythm of her speech was so similar to Sherrilyn’s voice, he thought it must be a recording. In the next scene, as Deavere Smith donned orange waders to become a 6’4″ 300-pound Native American fisherman, we were all willing to suspend any disbelief.

More important, Deavere Smith has chosen a story that’s best told from numerous points of view. The phrase “school to prison pipeline” was coined as early as 1998 to explain how zero-tolerance school discipline policies were leading students of color to be suspended at much higher rates than white students, and that school suspensions correlated to arrests later in life. But even the connection between police officers in schools and racial disparities in the US prison population only scratches the surface of these complex issues. Deavere Smith’s characters talk about urban poverty, absent parents, police brutality, drug abuse, the effects of trauma on children, the legacy of segregation, and the significance of the Confederate Flag. These are intimate, authentic portraits. Playing an emotional support teacher from Philadelphia, Deavere Smith relates stories of kids with bizarre behavioral issues bearing a strong resemblance to those shared by Erhardt’s mother over many decades teaching the same demographic. Sadly, many of her former students are now in prison.

Facing a challenge as complicated as “Why is American society failing so many Americans of color?” it’s hard to know where to start. In a sense, Notes From The Field starts everywhere: the Yurok Indian Reservation, the schools of Stockton, CA, the streets of Baltimore, the Capitol Building in Columbia, South Carolina. Anyone who’s worked on school to prison pipeline issues knows it’s hard to know where to start. “First, reform American education. And the prison system. And an economy that provides few opportunities for low-skilled workers. And end racism.” But Deavere Smith isn’t content with just providing a nuanced and moving picture of an impossible set of problems—she wants to fix them. More to the point, she wants us to be engaged in fixing them. To scaffold this, the play invites us into an implicit arc of witnessing, civic reflection, and taking action.

Witnessing

One of Deavere Smith’s characters is Kevin Moore, who recorded video of Freddie Gray’s arrest and transfer into the police van. In the interview she recreates, Moore explains that he was detained by Baltimore police after releasing his video, but that he was grateful for help from Copwatch, an organization that trains citizens to observe and record law enforcement actions, especially for buying him multiple cameras. Deavere Smith clearly believes our power to witness and to share what we see can help change the equation around police abuse of power as cameras and the power of sousveillance run as a theme through the performance.

But the videos she cites show how complicated that equation is. In the video Moore shot, we hear him reassuring Gray that everything will be okay, because he’s getting the arrest on tape. But Deavere Smith ends the scene by showing us the photos of the six officers who were acquitted of wrongdoing, or had charges dropped, in the killing of Freddie Gray. Video shot by Feidín Santana led to officer Michael Slager’s indictment for murdering Walter Scott, but video of Eric Garner’s death at the hands of Staten Island police led to no officers being indicted, but to the arrest of Ramsey Orta, who shot the video.

Video leaves us not with justice, but with an indelible image. The image likely to stay in our minds is that of a black high school student being thrown to the ground by Ben Fields, a white police officer (and school football coach) who drags her out of a classroom. Deveare Smith uses the footage as the backdrop of an interview in which the young woman who shot the video of her classmate explains how she was arrested and held in an adult jail for taking the footage. The ubiquity of citizen video creates a steady stream of unflinching videos that demand we don’t turn away, and Deavere Smith’s work holds our head steady and eyelids open.

The play itself functions as a radically deep form of witnessing. It concentrates the affective experience of witnessing for its audience by taking stories and videos and presenting them with careful curation and delivery. Deavere Smith’s acting threads together the individual elements in the school to prison pipeline and the current events that exemplify their problems. Breaking through what otherwise might be perceived as a collage of statistics and headlines associated with Black Lives Matter, she re-humanizes the people at the heart of these stories and invites us to walk in their shoes. The hope is that this will touch the audience in a way that an isolated video, protest march, or social media campaign cannot.

Civic Reflection

After a riveting 80 minutes of vignettes in different voices, Act Two of the show asks the audience to break into 15 person groups and to reflect on the issues raised and what we, as individuals, could do to address them. While it may be radical to insert a group discussion into a performance, sitting in a room full of well-meaning, progressive Cantabrigians who care deeply about making change but have no idea what to do is an awfully familiar experience for many of us at the Center for Civic Media, and likely for most of the audience.

Rather than prescribing solutions, we are asked to reflect on something larger than ourselves—an effect that is often the mark of a good work of art. This may be the show’s core purpose: civic reflection. We know this kind of reflexivity and analysis is a potent civic skill. There is also a movement-building “public narrative” invoked: a story of self, of us, and of now [pdf]. For those privileged enough to attend the play, we witness those directly affected by the issue and then Act Two’s facilitators ask us step into the Deavere Smith’s shoes as interviewer. We project our own perspectives and hear those of the others in our group. And we try to deepen our appreciation of the issue in a way that will cement its effect on us beyond the theater and give us a sense of urgency.

Taking Action

In a vignette late in Act One, a schoolteacher explains that she cannot solve the problems of the whole education system, so she works to save one child. Deveare Smith calls on us to repeat this phrase: “save one child.”

That’s a tough call to action. We are educators, but the students we work with aren’t ones in need of saving—do we answer the call by teaching at a community college? An under-resourced high school? Given the early start to the pipeline, do we teach kindergarten or preschool? Ethan’s sister is foster mother to a child born to a drug-addicted mother—he has a sense for the incredible sacrifice that can be required to save a child. Erhardt’s sister teaches theatre to urban youth hoping to provide the same outlet for truth Deavere Smith’s work does—but opportunities for such work are few and often poorly supported. How much must we do? How much can we do?

It will take revolutions in thought and policy to address the issues at the core of the school to prison pipeline. Vignettes like the schoolteacher scale the overwhelming task down to what others are doing to make a difference in their small corner of society. Bravely recording violent assaults by authority figures and not giving up on kids that need mentors the most are modeled behaviors that we might strive to emulate. There is not a clear “ask” embedded in the piece,* but it is a starting point that angers the audience and forces us to ask hard questions—a mighty accomplishment.

The play ends with Deavere Smith as Representative John Lewis. His story as a leader in the Civil Rights Movement is powerful and offers a vision of reconciliation with our racist past. He is also a symbol of our representative democracy. We elect people with the hope that they will fix these types of problems. The call to action implies we are all stakeholders—the radical and the procedural—that it will take all of society and we can’t give up on any institution or any person—like the teachers in the piece refuse to do.

*An Educational Toolkit [pdf] and a guide to local resources are available on the ART’s website to help folks “get involved.”